I saw this coming.

Recently the New York Times reported that, “The Hottest Gen Z Gadget Is a 20-Year-Old Digital Camera.” One 18 year-old, “documented prom night with an Olympus FE–230, a 7.1-megapixel, silver digital camera made in 2007 and previously owned by his mother.” A 22 year-old, “returned to her mother’s digital camera, a Canon PowerShot SX230 HS made in 2011,” posting on Instagram, “grainy, overexposed photos of herself wearing denim miniskirts and carrying tiny luxury handbags.”

Friends, this is just Digital Lomography.

Let’s flash back to a little before the turn of the century, slightly before the era these young folks’ cameras hail from. Photography, as a hobby, was arguably on the wane. Those who took photos socially generally used a point-and-shoot 35mm or APS camera, or just picked up a disposable camera at the drug store. More serious photogs used an SLR. Most of these, especially the SLRs and point-and-shoots, took consistent, focused and well exposed pictures with almost no effort.

However, some folks also thought these effortlessly consistent photos were boring. In 1992 a small band of enterprising Austrian youth encountered a Soviet-era point-and-shoot that turned out to be much more unpredictable, and therefore interesting, than the typical Canon, Nikon, Minolta or Pentax. Still being manufactured in St. Petersburg, they optioned the rights to sell the Lomo LC-A in the West, and founded the Lomography Society.

Being the early days of the internet – without Instagram or even Flickr – it took a little longer for word to spread. But by the year 2000 these quirky film cameras had inspired scores of photographers, especially young Gen Xers, to embrace them and take up film photography. Not only was this an act in defiance of highly refined Nikon 35mm SLRs, but also in defiance of the new technology of the digital camera. “Don’t think, just shoot,” became the mantra, preferring candid, chaotic shots over the posed and perfected. Lomography capitalized by issuing additional models of cheapish, intentionally imperfect, plastic film cameras.

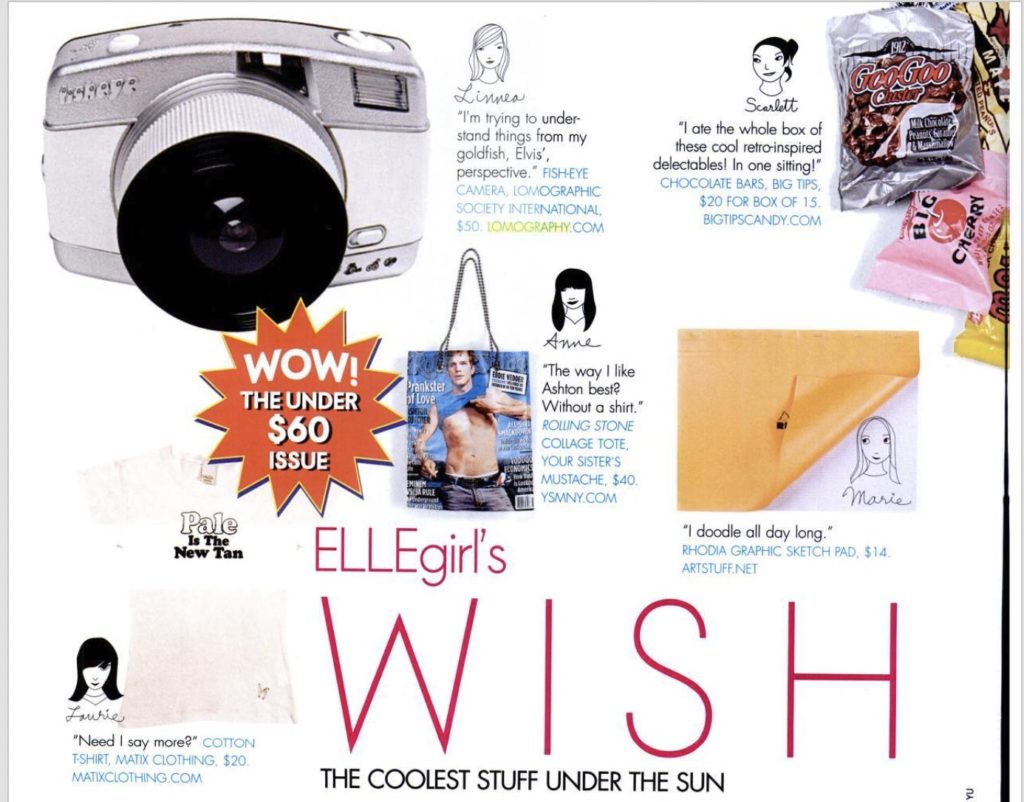

The trend was not exclusive to coastal hipsters, either. None other than ELLEGirl magazine featured Lomography cameras in at least three different product guide features from 2002 – spotlighting the clear plastic Lomo Action Sampler and blinged out shiny gold Lomo Pop 9 – and 2005, naming the Lomo Fisheye to its list of “the coolest stuff under the sun.” For a different demographic, the Oct. 2008 edition of Men’s Health Best Life dedicated a whole page to five different Lomography models, under the headline, “Perfectly Imperfect.”

In the intervening years film cameras have revived in popularity, with the interest spreading to all manner of vintage point-and-shoots, generally prized for their compactness, simplicity and, sometimes, quirkiness. For a time, price and accessibility was also a factor. If you couldn’t or didn’t want to spend $200 on a new Lomo LC-A, you might pick up an old Canon Sureshot at the thrift store or on eBay for just a few bucks. In the same way that the parents of today’s 18 year-old has a Nikon Coolpix tucked away in a junk drawer, a 2005 twenty-something’s folks probably had an Olympus Stylus (strictly 35mm) in a closet. Embracing forgotten and neglected film cameras has been both a pose against digital perfection, and an economic convenience.

Film Today: Still Fun, but Not As Cheap

Now, nearly 25 years into the film trend, the cache of cameras is starting to run low. The most desirable models, often touted by celebrities and Instagram influencers, can run well north of the price of a new iPhone. There are still plenty of less sought-after units to be found, but these plastic consumer items were never designed for longevity. With many approaching forty or more years old, finding a reliably functioning camera becomes a challenge. Or at least difficult to obtain for a thrift store price.

This parallels the revival of vinyl, which has, in turn, driven up prices. Pressing plants can barely keep up with demand for new records, while the supply of used ones is inherently limited, especially for more sought-after titles. This situation seems to be sparking renewed interest in CDs, which cost about half of an LP for new albums, and may be only a dollar or two for back catalog. It’s all a little ironic for those of us who bought vinyl in the 90s because it was cheaper than compact discs. But I digress…

Digicams: Film’s Cheaper Little Sibling

It should come as no surprise that the point-and-shoot digital camera is ready to step into its film brethren’s shoes. The dominance of the smartphone camera pushed this technology out of the spotlight, and out of most manufacturer’s lineups. Yet, the landscape and bargain bins are littered with ones bought during the 2000s heyday, when every family had at least one to document all the life events now ably recorded by iPhones and Google Pixels.

A 2007 Canon PowerShot arguably may be more technically competent than its 35mm Sureshot forebearer, but its color palette, light sensitivity and dynamic range pale in comparison to even a five year-old iPhone. And, yet, it has a certain aesthetic that is identifiable, in the same way of that Lomo LC-A in 1994 or Olympus Stylus in 2010. Nostalgia is no doubt, a factor, as is imperfection and unpredictability… and fashion (or trend).

In Praise of the Digicam Revival

The fact that this new digicam trend was predictable, and follows a familiar pattern, does not mean it is frivolous or risible; or at least no more so than the earlier film photo trends. When I say I saw it coming, I’m making no claim to special knowledge or clairvoyance. I only read the clear signs, seeing the dwindling supply of functioning film point-and-shoots, while encountering a ton of once desirable digicams that exhibit far more quirks and imperfections than what we’ve become accustomed to, today. The most notable fact is that the digicams sell for small fractions of their original price, or can be obtained for near-free from friends or relatives cleaning out their junk drawers.

I think it’s fantastic that young people are snapping up these once-cutting-edge pieces of consumer electronics. It’s fun to mess around and take hundreds of wacky photos in the hope that maybe a few turn out to be special. Plus, it’s way cheaper than taking hundreds of 35mm photos today – the price of film continues to rise, and the number of places to develop film have greatly declined in the last decade. Moreover, I like anything that keeps these neglected cameras out of landfills.

¡Viva el Digital Lomo!

Comments are closed.